All Endings Are Beginnings, and All Beginnings Are Endings

Saturday, November 23, 2019 at 06:40PM

Saturday, November 23, 2019 at 06:40PM

Throughout this human life, I have moved between the world of the artist-storyteller and that of the design practitioner: this tidal action has given me many opportunities to explore and reflect upon philosophical ideas about our essential human nature, as expressed by people like Descartes, Locke, Rousseau, Freud, Jung, Buber, etc.

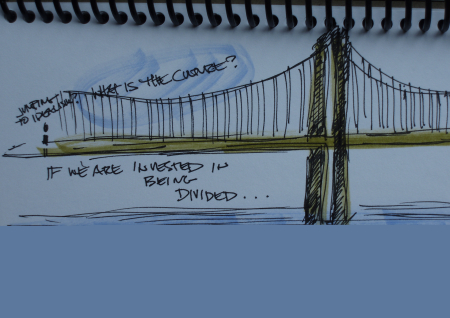

One of these ideas -- that of Cartesian dualism--asserts (back of the napkin) that humans have split our thinking "rational" self off from our feeling/intuitive "being" self, and thus, cannot accurately perceive or intervene to prevent the negative effects of our behavior on ourselves and on the world around us. Outside academia, the shorthand for this bacony-cheesy concept is "the mind-body split."

When I was in graduate school, Cartesian dualism was a perennial topic of conversation, and was sometimes proffered as a root cause of environmental degradation, and as justification for imposing environmental restrictions on people. This was a stance I found problematic, as I do not believe that blaming people is effective, nor should anyone be imposing top-down solutions on the complex, messy process of being human. Life is complex, and our responses --especially if we are working with design problems like poverty, addiction, environmental degradation, etc. (the so-called "wicked problems")-- must take this complexity into account.

Working with wicked problems begins with the recognition that developing effective responses involves a process of engaging those people feeling a direct impact, and working with them to explore and address aspects of the problem they can control in a generative, context-specific manner. Top down solutions interfere with this process and so--ecologically speaking - they are categorically inappropriate.

That said, as a designer and an artist, I have found Cartesian dualism to be a very useful concept in applied ecological design as a starting point for evaluating potential clients. I do this in many ways, one of which involves paying close attention to how a potential client initially sets a design problem. Uncovering the problem set involves listening for and observing how a client describes the design issue of concern, and noticing whether there are any obvious types of Cartesian disconnections being expressed.

For example, is the design problem being presented in emotional language? "Climate change! Climate change! The world is going to end in 12 years! We must do something! Please help us!" (NOTE: in using the term "climate change" as the problem du jour, I am NOT saying "climate change" is a legitimate framing of a highly complex problem: from the standpoint of ecological intelligence & design, it most certainly is not. I am using the term because it is common parlance at this historical moment, and reflects the type of simplistic emotional rhetoric that passes for critical thought in the vast majority of early 21st century policy documents, as well as being a ubiquitious presence in political and social commentary.)

Or is the design problem parsed in dry, boring, legalese? "...whereas, we, the members of the faculty committee, do hereby assert that climate change is a serious problem, one we must focus the curriculm on, and we must ensure that our students place this concern at the center of their academic studies."

Or, is the design problem being expressed as a blend of concrete description and concrete solution? "We can see that our local water table has been dropping for 15 years, and the last 11 years have been increasingly colder than the 40 years before that, combined. We're not sure what's causing these changes, but we see a need to help low income and elderly folks reduce energy costs and make their homes more comfortable..so we'd like to do something along those lines."

Each of these responses provides information about where a potential client is, psychologically and emotionally, in their relationship with ideas, with other people, and with their environment. How people talk about the problem(s) which concern them also gives me some clues about how they may respond to being challenged with new information - which comes with the terriority of complex change.

For example, the first client group's description reflects emotionality and baseline stress. They are reactive, not responsive, and their stance reflects a high degree of polarization. They are likely to spend a lot of time defending themselves from new information, and are unlikely to have the internal capacity to respond calmly to being challenged on their framing of the design problem. More likely than not, we'd never get past an initial conversation.

In contrast, the second client group is very emotionally detached -- a stance which, collectively, will hamper their ability to develop their design project and to generate any enthusiasm for what they're doing. These types of groups often have deep, multiple hidden agendas which are expressed as a highly intellectual stance toward an abstract problem. As a design consultant, I can often feel their boredom, disinterest and tight control viscerally...and it is toxic. Unless a group with this presentation is open to connecting head with heart--a nuanced process which takes time to engender--their internal dynamics can result in one or two people pushing on a string and the rest of the group passively resisting the process. In such a scenario, the design consultant can end up functioning like a battery for the string pushers. Pass.

And then there is the third potential client: this group acknowleges local (microclimate) change and indicates both concrete awareness of what has changed, and why it's of concern. If I asked--and I would--they would likely be able to articulate this in some detail. Furthermore, they don't appear to be looking for the heroic angle, such as "we're fighting to save the earth!" nor are they reactively on the march for a scapegoat. They're grounded--literally--in where they are. And they're ready to take responsibility for doing something positive and concrete to make things better. I'd engage with them.

Beyond making initial client assessments, listening for these types of Cartesian splits --which often announce themselves tonally and reflect self-self, self-other, or self-environment disconnections-- informs how I pace group work, anticipate conflicts, and ask questions throughout a design project.

Using the concept of Cartesian dualism to obtain design information and improve my practice, rather than as a way to blame and control people, has had many positive effects on my personal and professional life. It has allowed me to have much more interesting conversations about design and ecological literacy. It has enabled me to work with a much more diverse range of clients, and on a much more diverse range of issues than I would have otherwise. And it has helped me develop my emotional range and courage as a design practitioner. This, in turn, has influenced my creative work in many wonderful ways.

At this time in my life I am turning away from technical design work, and toward my own creative projects. As part of making this change, I am archiving this blog. Going forward, you can find my work at www.sequoia.earth.

Thank you for being my audience over the years at this very sparsely written blog. I have been honored to have had a small, dedicated following, and I hope you will enjoy some of my longer literary works as they appear.

sequoia dot earth | Comments Off |

sequoia dot earth | Comments Off |